Since the birth of UE Local 150, the North Carolina Public Service Workers Union, in 1998, one of its central goals has been the repeal of North Carolina General Statute 95-98, which outlaws collective bargaining and union contracts for all state and local public employees. Local 150 delegates and leaders often tell other UE members that this law is a “Jim Crow law.” For Black History Month 2014, the UE NEWS asks, “What is Jim Crow?”

GS 95-98 was passed in 1959, when racial segregation and discrimination were in full force in North Carolina and across the South and black people had no voting rights or political representation. It was one more measure to keep black workers down and prevent the growth of unions. The collective bargaining ban was born as part of Jim Crow, the system of political disenfranchisement and racial discrimination that reigned across the South, and to a significant degree in much of the North, from the turn of the last century until the victories of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.

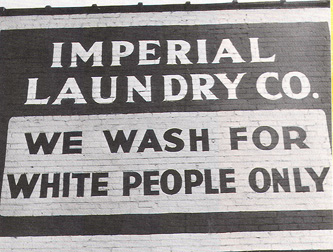

The term “Jim Crow” comes from minstrelsy, a form of entertainment very popular in the 1830s and succeeding decades. Minstrel shows featured white performers in blackface in what were claimed to be African American songs, dances and skits. The jokes were at the expense of black people, who were portrayed as superstitious, lazy, happy-go-lucky buffoons. A minstrel performer from New York City, Thomas D. Rice, introduced a song-and-dance number in 1828 titled “Jump Jim Crow” and he continued to portray the character Jim Crow throughout his career. (The logo for this article features an 1832 drawing of Rice as Jim Crow.) Jim Crow entered the language as an insulting term for African Americans, and decades later, when Southern states began to impose segregation, the separate accommodations for blacks were called the “Jim Crow section” or the “Jim Crow men’s room.” The name was soon applied to the entire system, and the laws that mandated it were called Jim Crow laws.

BEFORE JIM CROW

After the Northern victory in the Civil War, pro-slavery forces in the South did not meekly accept defeat but attempted to virtually re-enslave African Americans through violence and repressive “black codes.” But in Congress, the Radical Republicans passed the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution and civil rights laws to protect black rights. With the South under military occupation by the U.S. Army and the U.S. Congress as an ally, the period of Radical Reconstruction (1866-77) was one of the most democratic in Southern history. Former slaves gained the right to vote, hold office, serve on juries, and receive education (although in separate schools). A federal agency, the Freedman’s Bureau, was empowered to protect the rights of black people, including the right to be fairly compensated for work. Poor whites also benefited from these reforms. Reconstruction was not without flaws, and it met violent resistance in the form of lynching by the Ku Klux Klan and similar white terrorist groups.

Reconstruction ended in the deadlocked presidential election of 1876. Republicans made a deal in Congress with Southern white Democrats: in exchange for Southerners agreeing to give the presidency to the Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, Republicans withdrew federal troops from the South. The restoration of conservative Southern white rule was called “Redemption”, but it did not immediately lead to extinguishing black citizenship. Southern states elected 10 black members to the U.S. House of Representatives after Reconstruction, the same number elected during Reconstruction. In North Carolina between 1876 and 1894, 52 African Americans served in the state general assembly. White politicians, except for the most extreme racists, competed for the black vote and negotiated alliances with black leaders. During this period, although racism, injustice and racist violence were widespread, Southern blacks and whites often interacted on the basis of mutual respect and even equality. Such interaction was strictly forbidden after 1900.

THE PEOPLE’S PARTY

Politically the Jim Crow era was the era of the “Solid South” – one-party rule by the “white man’s party”, the Democrats. But in the 1890s much of the South had a three-party system, and competing for white and black votes were Republicans, Democrats, and a new force, the People’s Party or Populists. The Populists were a party of small farmers and workers organized on an anti-corporate platform, and from 1891 to 1904 the Populists elected 45 members of Congress, all from the West and the South. The Populists supported labor unions and fought for labor rights. In the South they appealed to black voters on the basis of the common interests of poor and working people against the rich.

While there was racism among the Populists, they recruited black members, had several black spokesmen, and allied with blacks organized in the Colored Farmers’ Alliance, the Knights of Labor, and in some cases with black Republican politicians. Tom Watson of Georgia, a key leader of Southern Populism, urged his followers to “wipe out the color line, and put every man on his citizenship irrespective of color.” The movement’s finest hour may have been during the 1892 Georgia election, when 2,000 armed white farmers, some riding all night, rushed to the defense of H.S. Doyle, a young black preacher and Populist organizer whom Democrats had threatened to lynch.

The threat of a black-white working class alliance frightened Southern capitalists, big landowners and leaders of the Democratic Party, and led them to embrace the extreme racist faction and its program. Across the South in the 1890s they waged a propaganda campaign of the most vicious race hatred, combined with election tactics that historian C. Vann Woodward summarized as “fraud, intimidation, bribery, violence and terror” against Populists, Republicans, and black voters. Elections were blatantly stolen, and Democrats murdered several black Populists in cold blood. By thoroughly undemocratic means, the white elite “redeemed” the South for a second time, this time to institute a new regime of racial oppression as brutal as slavery.

The North was complicit in the rise of Jim Crow. The Supreme Court had struck down most of the civil rights laws of Reconstruction and failed to enforce the 14th and 15th Amendments. Racism was spreading in the North, including pseudo-scientific intellectual theories of the “superiority of the Anglo-Saxon race”. In 1898 a Republican president went to war with Spain to seize the colonies of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. There followed a bloody three-year war to crush the Philippine independence movement, in the name of white supremacy. Northern elites no longer had the will or the moral standing to oppose racism in the South.

VOTER SUPPRESSION, RACIAL OPPRESSION

The first priority of the new Jim Crow state governments was depriving black people of the vote. Since the 15th Amendment said voting rights couldn’t be denied on the basis of race, they used indirect tactics such as the poll tax, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses. Then came a flood of perverse laws and regulations aimed at segregating the  races. These included separate railroad cars, streetcars, restrooms, drinking fountains and prisons. Elaborate rules dictated strict separation of the races in housing, healthcare, public entertainment and nearly every aspect of life. In schooling and other areas, facilities and services for black people were far inferior to those for whites. Through the early decades of the 20th century, Southern states continued to pile on new segregation rules which were, in Woodward’s words, “constantly pushing the Negro farther down.” Racist legislation was accompanied by racist violence, with lynchings and in some cases mass murder of African Americans.

races. These included separate railroad cars, streetcars, restrooms, drinking fountains and prisons. Elaborate rules dictated strict separation of the races in housing, healthcare, public entertainment and nearly every aspect of life. In schooling and other areas, facilities and services for black people were far inferior to those for whites. Through the early decades of the 20th century, Southern states continued to pile on new segregation rules which were, in Woodward’s words, “constantly pushing the Negro farther down.” Racist legislation was accompanied by racist violence, with lynchings and in some cases mass murder of African Americans.

Ending Jim Crow required decades of resistance in many forms, mostly by African Americans in the South. The resistance included courageous union organizing by Southern workers in the 1930s and ‘40s against great odds. The tide of national opinion finally began to turn during and immediately after World War II, making possible large-scale protests against Jim Crow such as the 1955-56 Montgomery bus boycott and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. This was one of the greatest moral crusades in American history, directed against one of the greatest evils in our history.

The legacy of Jim Crow is still with us in many forms. Housing and schools are still segregated in many places, black people often don’t receive equal education or job opportunities, or equal treatment by the police and courts. But we must remember that the original purpose of Jim Crow – and long before that, of paying wages to white workers while making slaves of black workers – was to keep working people from uniting. Laws that deprive workers of their rights to organize, bargain collectively, and strike are also a legacy of Jim Crow. We need to overcome all of this.

READ MORE

The Strange Career of Jim Crow by the influential Southern historian C. Vann Woodward, first appeared in 1955. A very good explanation of Jim Crow and how it arose.

To Make Our World Anew: A History of African Americans covers the entire sweep of black history (2000) edited by Robin Kelley and Earl Lewis, with chapters by nine other excellent historians. (See Volume II here.)

Civil Rights Unionism: Tobacco Workers and the Struggle for Democracy in the Mid-Twentieth Century South by Robert Korstad (2003) is the story of the rise and fall of Local 22 of the Food, Tobacco and Agricultural Workers (FTA) at R.J. Reynolds in Winston-Salem in the 1940s, against all the obstacles of the Jim Crow system of “racial capitalism.”

The works of W.E.B. DuBois, the preeminent African American intellectual and freedom fighter in the first half of the 20th century, provide a rich education in the history of black people, including the Jim Crow era. These include Dusk of Dawn, The Souls of Black Folk, his Autobiography, and his great historic work on the Civil War and Reconstruction, Black Reconstruction in America.