Fifty years ago, African-American sanitation workers in Memphis stood up for dignity, striking to demand recognition of their union — and their humanity.

The strike pitted over a thousand sanitation workers, who as public-sector workers in the right-to-work state of Tennessee had no legally protected right to collective bargaining, against an entrenched white power structure that held African-Americans in contempt and loathed unions. The workers’ determination to fight for their rights drew support from the African-American community in Memphis, young people, the national labor movement and eventually, the nation’s most well-known civil rights leader, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who was tragically murdered while in Memphis supporting the workers’ struggle.

A Committed Core of Workers

For the sanitation workers, the strike was the culmination of almost a decade of organizing. Led by a sanitation worker named T.O. Jones, whose dedication to the union was unwavering, workers had tried to organize with the Teamsters in 1960, and to form an “Independent Workers Association” in 1963. AFSCME Local 1733, the number chosen to honor 33 sanitation workers who were fired during the IWA organizing attempt, was chartered in 1964.

Sanitation workers had plenty of reasons to join the union. The work was dirty and dangerous, the hours were long and unpredictable, and the pay was low. Memphis residents were not required to bag their garbage or take it to the curb, so sanitation workers loaded the garbage by hand into tubs and barrels, which they then carried across lawns to the trucks. Workers faced arbitrary and condescending treatment not only from white bosses, but from many white residents.

Among the strongest union supporters were workers who had worked in union shops, in Memphis or elsewhere, or who had served in the military during World War II or the Korean War. Jones had served in the Navy and worked in shipyards in Oakland, California, and when he began organizing, he received advice and assistance from African-American trade unionists in Memphis’s industrial unions, among them the United Rubber Workers (URW) at the Firestone plant and the United Auto Workers (UAW) at International Harvester.

Fear kept many other workers away from the union, however. The city was perfectly willing to fire workers who tried to assert their rights, and when Local 1733 threatened a strike in 1966, the city arranged for scabs and got a court injunction against Jones and other local leaders. Workers abandoned the strike, and this defeat nearly destroyed the union, with only about 40 workers continuing to pay dues in the period leading up to 1968.

Still, Jones and other persisted. The threat of a strike, and the very existence of the union, prompted the city to offer modest improvements, including better equipment and a 10-cent raise.

“All us labor got together and we was going to quit work till we … could get justice on the job”

Henry Loeb was elected mayor of Memphis in 1967. As Commissioner of Public Works, from 1956-60, he had imposed a variety of “efficiencies” at sanitation workers’ expense, including using the cheapest equipment. He had served a previous term as mayor, from 1960-63, winning election in 1959 as a staunch segregationist. His 1959 endorsement from the AFL-CIO split an alliance between labor and the African-American community that had won improvements for both workers and African-Americans in the 1950s.

Upon taking office in January 1968, Loeb ended the informal bargaining relationship that Jones had been able to develop with management in the Department of Public Works. He also reinstated an old policy of his of sending workers home with only two hours pay on rainy days. During the previous administration, workers had been allowed to work or wait until the rain cleared up, with no loss of wages. On January 30th, 21 sewer and drainage workers were sent home under Loeb’s policy.

Then on February 1, two sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were killed while taking shelter from driving rain inside a faulty garbage packer. Jones had previously taken a grievance to the Department of Public Workers commissioner, asking that this particular truck no longer be used.

Workers’ anger at the lost pay for the sewer and drainage workers, the meagre benefits offered to the families of Cole and Walker, and years of mistreatment by management, built up over the next ten days. On Sunday, February 11, between 700 and 900 workers gathered to talk about strike action.

72-year old Ed Gillis attended the meeting. He reported that the decision to strike didn’t come from the union leaders, but from the workers. “It wasn’t T.O. Jones. It was all of us labor got together and we was going to quit work till we got a raise and got a better percentage, see, and could get justice on the job from the way they’s treating us.”

“It was clear that white workers would not have been treated this way”

Between Mayor Loeb’s intransigence and the workers’ solid determination to be recognized as human beings, the strike was not destined to be settled quickly. The workers, however, maintained organization and discipline throughout the more than two months of the strike, with daily noontime meetings at the URW Local 186 hall, from which they would march downtown, many with placards which famously declared “I Am a Man.”

AFSCME International President Jerry Wurf arrived in Memphis on February 18th. Wurf had been elected four years previously as part of an insurgent slate of younger workers and staff that pushed that union in a more progressive and activist direction. Wurf and his new administration integrated what had been separate locals for white and African-American workers, hired African-American organizers, and aggressively organized workers throughout the country. After fruitless meetings with Loeb, Wurf concluded that “it was clear that white workers would not have been treated this way” — that the strike, which AFSCME had been at pains to paint as a labor issue rather than a racial issue, was actually both.

The strike became a rallying point for Memphis’s African-American community. African-American Baptist ministers convened on the second day of the strike to intervene on behalf of the workers. On February 24, the same day that the city obtained a draconian injunction against AFSCME which essentially made the strike illegal, more than 100 African-American ministers from across the city gathered. The support group they formed, Community on the Move for Equality (COME), would play a crucial role in mobilizing community support for the sanitation workers.

One of the most dynamic leaders of COME was Rev. James Lawson. A former chair of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s direct-action committee, Lawson had accepted a position as minister at Centenary United Methodist Church and moved to Memphis in 1962. Deeply committed to both non-violence and economic justice, he threw himself into the struggle, bringing both nonviolent militancy and a broad social vision which resonated with the wider African-American community.

The noontime union rallies and marches were soon supplemented by nightly mass meetings held in various churches, where community workers and community supporters would sing, pray, share news and strategize. As historian Michael K. Honey puts it:

Mass meetings gave the movement its own means of communication—keeping people informed about what to do next, the status of negotiations with the city, where to go next and when to meet. They provided a forum for discussing a strategy for action, for connecting generations, for spiritual awakenings.

Lawson described the importance of the mass meetings as “the psychological arena for people, because we don’t deny death or deny pain, we don’t deny the struggle [in] the world in which we live, we … help provide folk with ways of understanding it and then dealing with it … in a constructive fashion.”

As the strike continued into its second month, the cause of the workers was increasingly taken up by African-American youth in the city. Many of them, inspired by the Black Power movement, were far less patient than the ministers, a tension that would play out when King came to Memphis, although King himself had always insisted that a sufficiently militant nonviolent movement could win youth attracted to armed self-defense over to the cause of nonviolence.

The failure of AFL-CIO unions to confront racism head-on meant that the sanitation workers were, sadly, unable to count on much support from their white fellow union members in Memphis, especially as racial tensions in the city escalated. However, the workers did receive crucial support from some unions. URW Local 186, which had a large African-American membership, continued to open their hall for strike meetings. Tommy Powell, the white president of the Memphis Labor Council, also provided crucial support for the strike. A former college football player who lost his scholarship for organizing his fellow players to strike against mistreatment by their coach, Powell had become a trade unionist in a meatpacking plant where he learned that uniting African-American and white workers was the only way to get anything from the boss.

Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Poor People’s Campaign

In December 1967, Dr. King had announced a new campaign, to bring attention to issues faced by poor Americans of all backgrounds. He envisioned a march on Washington and a campaign of massive civil disobedience to demand jobs, housing and education. In order to achieve this, King called for a “new and unsettling force,” a multi-racial “nonviolent army of the poor, a freedom church of the poor.” In his last Sunday sermon, he preached:

We are coming to Washington in a poor people’s campaign. Yes, we are going to bring the tired, the poor, the huddled masses … We are coming to demand that the government address itself to the problem of poverty. We read one day: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights. That among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. But if a man doesn’t have a job or an income, he has neither life nor liberty nor the possibility for the pursuit of happiness. He merely exists … We are coming to ask America to be true to the huge promissory note that it signed years ago. And we are coming to engage in dramatic non-violent action, to call attention to the gulf between promise and fulfillment; to make the invisible visible.

In the sanitation workers’ struggle in Memphis, King saw a microcosm of what he had envisioned for the whole country: a community coming together around the economic struggles of poor working people, linking that economic struggle with a community struggle for freedom.

“If you believe in right, stick with it”

When King first came to Memphis on March 18, he shocked both labor and civil rights leaders by proposing a general strike. “I tell you what you ought to do,” King said, “and you are together here enough to do it: in a few days you ought to get together and just have a general work stoppage in the city of Memphis!” King agreed to return to lead a non-violent march, protest, and general work stoppage on Friday, March 22.

Had this happened, it would have been the first general strike in the U.S. since 1946, when working people, many of them newly organized into the multiracial unions of the CIO and feeling the power that came from unity, shut down six U.S. cities in solidarity with local strikes.

Instead, Memphis was shut down that day by a freak snowstorm, which also prevented King from getting there. And when he returned the next week to lead a rescheduled protest on March 28th, it was marked by the tensions between militant youth and nonviolent ministers, massive police brutality, tear gas, and the police shooting of a 16-year old African-American man. King, barely a week before his death, was mocked and pilloried by the white press in Memphis as a hypocrite and a coward.

King returned to Memphis on April 3, determined to lead a non-violent march on Monday, April 8. Meeting with young militants the next morning, he asked them to accept nonviolent discipline and serve as marshals. The movement “needs young people willing to lead,” he told them.

The night of the 3rd, King gave what was to be his last speech at Mason Temple, as storms raged outside. He linked the struggle in Memphis to liberation struggles around the world:

The masses of people are rising up. And wherever they are assembled today, whether they are in Johannesburg, South Africa; Nairobi, Kenya; Accra, Ghana; New York City; Atlanta, Georgia; Jackson, Mississippi; or Memphis, Tennessee — the cry is always the same: "We want to be free."

He recounted the history of the civil rights movement in Birmingham, Alabama, where Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor turned dogs and water hoses on nonviolent marchers. King proclaimed that the movement was going to bring that kind of discipline, and win that kind of victory, in Memphis. He condemned the anti-strike injunction:

Somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech. Somewhere I read of the freedom of press. Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for right. And so just as I say, we aren't going to let dogs or water hoses turn us around, we aren't going to let any injunction turn us around. We are going on.

King spoke about the importance of African-Americans building their own economic base instead of supporting companies that refused to hire African-American workers. He told his audience, “we've got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end” and that “either we go up together, or we go down together.” He spoke of his own brush with death ten years earlier, when he was stabbed by a mentally ill woman at a book signing, and of his gratefulness that he survived, for had he died he “wouldn't have been in Memphis to see a community rally around those brothers and sisters who are suffering.”

King concluded his final speech with what would come to be eerily prophetic words:

Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!

Sanitation workers were energized and uplifted by King’s words, which calmed some of their own fears. “King was like Moses,” recalled sanitation worker James Robinson. “A lot of that stuff he was talkin’ about was true. A lot of that stuff was gonna come to pass. You can’t keep treatin’ people wrong, you gotta do right some time.” Said striker Clinton Burrows, “He made it very clear that he didn’t fear any man. That is a good spirit, to not fear any man. If you believe in right, stick with it.”

Assassination and Aftermath

King was killed the next day by James Earl Ray. Outrage swept the world, and many UE locals held work stoppages. The UE News reported that “Districts and Locals across the country immediately issued statements and expressions of sorrow and shock. Telegrams were sent to the Mayor of Memphis charging that the city’s refusal to bargain with its 1300 sanitation workers was responsible for Dr. King’s death, and calling on him to recognize and bargain with the union.”

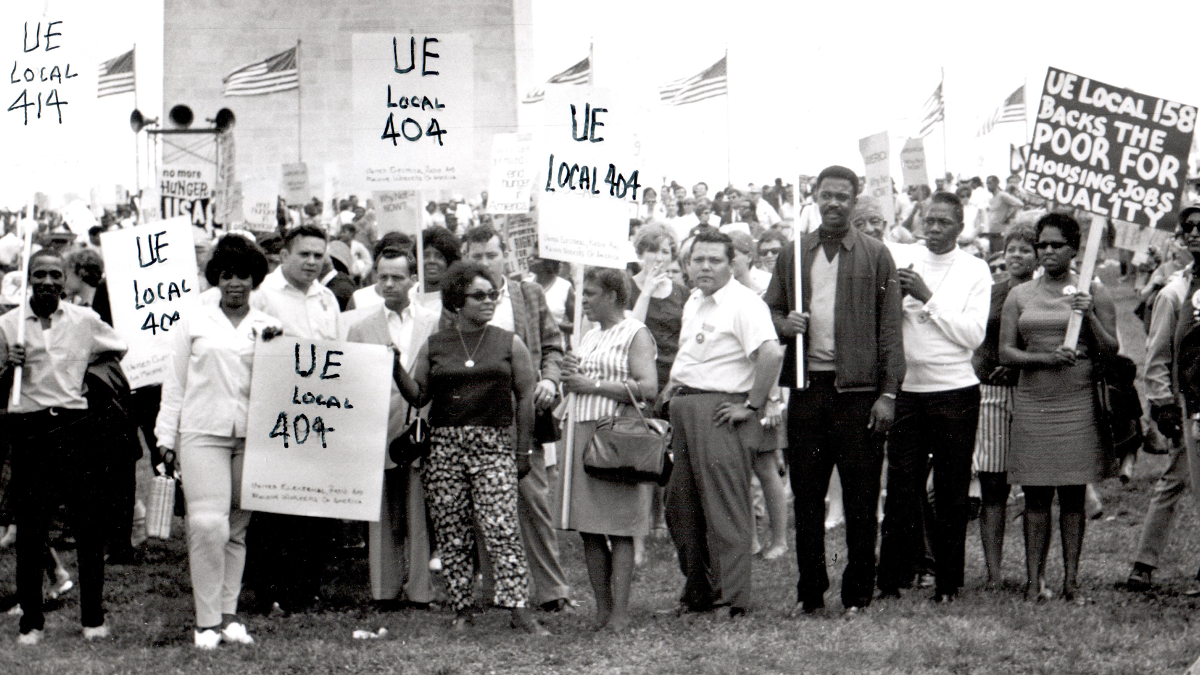

The April 8th march went on, and King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, came to Memphis to lead it. Tens of thousands of people joined the march, including a delegation from UE District One and hundreds of other trade unionists who had come in from around the country. Some of the militant youth King has spoken to on the morning of his assassination served as marshals, and the march was fully nonviolent, as King had hoped.

UE Field Organizer Jack Hart, a member of the District One delegation, told the UE News “I heard the same thing in Memphis that you hear in Philadelphia, New York, Chicago or any other major city: police brutality. The white community had turned its head and closed its ears to the cries of this black community about police brutality, discrimination and exploitation, but the white community should know that as long as the garbage collectors are held back, all city employees are held back.”

AFSCME Local 1733 finally achieved a contract settlement on April 16th. It included union recognition, dues checkoff, seniority for promotions, a grievance procedure and a nondiscrimination clause. Wages increased 10 cents on May 1st and another five cents on September 1st.

The Poor People’s Campaign went forward. Nine regional caravans brought thousands of participants to “Resurrection City,” an encampment in Washington, DC: the “Eastern Caravan,” the “Appalachia Trail,” the “Southern Caravan,” the “Midwest Caravan,” the “Indian Trail,” the “San Francisco Caravan,” the “Western Caravan,” the “Mule Train,” and the “Freedom Train.” They were joined by 50,000 people, including a sizeable UE delegation, on June 19th, for a Solidarity Day Rally for Jobs, Peace, and Freedom.

UE News reporter Charles Kerns joined a busload of UE Local 158 members and reported on some of their thoughts for the UE News. Shop steward Dottie Atkerson told Kerns, “I feel I should participate because I know what it is to be poor. I grew up in poverty. I know what it is to count pennies—and also to fulfill Martin Luther King’s dream.” Local 158 member Donald Reed added, “I believe in the true cause of freedom, not only for Negroes but for all people. I think Martin Luther King’s cause was for all people.”

Despite the sizeable turnout for the Solidarity Day rally, the Poor People’s Campaign of 1968 did not fulfill Dr. King’s hopes to become “a new and unsettling force” on behalf of working and poor people, and the escalating costs of the war in Vietnam continued to drain resources from efforts to fight poverty. As UE General President Albert Fitzgerald told the 33rd UE Convention in September of that year:

You cannot have guns and butter at the same time in this country. You cannot have decent wages, hours, and working conditions; you can’t have decent homes and decent schools; you can’t have freedom for anyone in this country as long as our resources are going down the sink being expended in futile wars.

Carrying on King’s Legacy

Fifty years after the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike, UE member and allies are continuing his legacy.

Municipal workers in the South are still fighting low wages, unsafe conditions, and disrespect. UE Local 150 is organizing municipal workers in the state of North Carolina, where collective bargaining in the public sector is illegal under a Jim Crow-era state law. Local 150 is marking the 50th anniversary of the Memphis strike and King’s death by launching a campaign for a Municipal Workers Bill of Rights. (For more information on this campaign, see this recent Labor Notes article by Local 150 member Sarah Miles).

Rev. Dr. William Barber II, a long-time UE ally who spoke at the 2013 UE convention in Chicago, has left his position as head of the North Carolina NAACP to lead a new Poor People’s Campaign. The Poor People’s Campaign is organizing people from all backgrounds across the country for “a season of sustained nonviolent civil disobedience as a way to break through the tweets and shift the moral narrative” to issues of “how our society treats the poor, those on the margins, the least of these, women, children, workers, immigrants and the sick; equality and representation under the law; and the desire for peace, love and harmony within and among nations.” (Learn more about, and join, the new Poor People’s Campaign at poorpeoplescampaign.org)

As King said in his final speech:

Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with a greater determination. And let us move on in these powerful days, these days of challenge to make America what it ought to be. We have an opportunity to make America a better nation.

Learn more

Michael K. Honey’s excellent book on the Memphis strike, Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign, provided much of the background and quotations used in this article. To purchase from a unionized bookstore, and have part of the sales proceeds go to the workers’ strike fund, visit ilwulocal5.com/support and click on the link to Powell’s Books.

The 1994 documentary film At the River I Stand about the strike is available in a variety of formats at http://newsreel.org/video/AT-THE-RIVER-I-STAND.