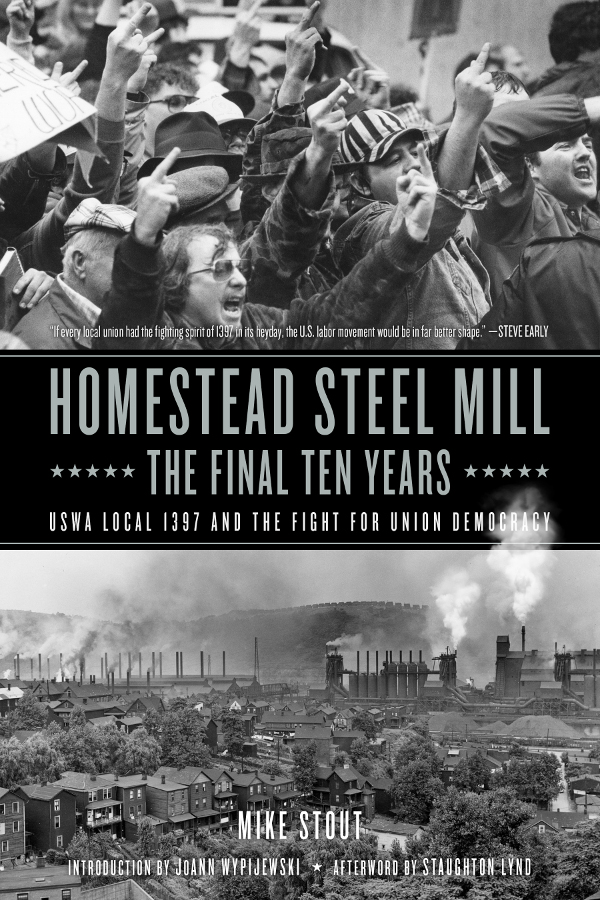

Homestead Steel Mill, The Final Ten Years: USWA Local 1397 and the Fight for Union Democracy

By Mike Stout

PM Press, 223 pages

$24.95 (paperback), $8.95 (ebook)

“Homestead” is one of those place names in U.S. labor history – like Haymarket and Flint – that carries a lot of meaning. The courageous 1892 struggle by the workers of the Homestead mill and their community, against robber baron Andrew Carnegie, his union-busting lieutenant Henry Clay Frick, and the Pennsylvania National Guard, ended in defeat for the workers and killed the idea that craft unions could succeed at collective bargaining in mass production industries. But in Mike Stout’s memoir of his life as a worker and union leader in the Homestead mill’s final decade, he makes clear that something of the rebellious spirit of 1892 survived. “For me,” he writes, “1892 and 1982 are part of a whole, two points on the same pole of resistance and spirit of solidarity that sprang up, thrived, and was eventually suffocated at the great Homestead steel mill.”

This book is the story of how an insurgent membership, organized as the Rank and File Caucus, took over a 6,000-member local of the United Steelworkers, ousting a conservative, do-nothing leadership. Local 1397 transformed itself into a militant, democratic, fighting local. They encountered a lot of resistance from the United Steelworkers International, headquartered a few miles away in downtown Pittsburgh, and the fierce opposition of their employer, U.S. Steel.

The caucus was started by three workers: Ron Weisen, who later became the local’s charismatic but sometimes mercurial president; John Ingersoll; and its real initiator, Michele McMills. University-educated and only 24 years old in 1976, McMills loved working in the mill and devoted her skills to building a militant, democratic workers’ movement. She also initiated the 1397 Rank and File newspaper, the scrappy, participatory caucus publication which became the local’s official newspaper after the Rank and File Caucus was swept into office with a landslide win in the 1979 local officer elections.

Unlike most of his co-workers, Stout was not a native of a Pittsburgh-area mill town. He was born in Lexington, KY, and after bumping around the country, working in various jobs including the post office, and honing his skills as a singer/songwriter in New York’s Greenwich Village, he got a job in the Homestead mill in 1977. There he soon became involved in the Rank and File Caucus, and became a griever (the USW word for shop steward). Eventually he was elected chair of the grievance committee (i.e., chief steward) for the entire plant. Stout describes in detail how he and his fellow grievers transformed a “cumbersome and repetitive” grievance procedure, in which the union was losing four out of every five arbitration cases, into a strong, effective union weapon. Under the Rank and File regime, the union started winning grievances and even most arbitration cases. The key, Stout says, was involving workers in their own grievances, and being aggressive in obtaining information that helped the union win.

The book is also a tale of worker resistance to deindustrialization: the destruction of millions of often unionized, relatively good-paying jobs in manufacturing. Local 1397 was at the heart of the resistance to dismantling most of the steel industry and other unionized industries. Homestead is located on the Monongahela River upstream from Pittsburgh. Up until the ’80s the “Mon Valley” was lined with steel mills. In the period covered by Stout’s book, most of the American steel industry disappeared because its corporate owners had for decades refused to reinvest in the mills, choosing instead to “take the money and run” to more lucrative investments. On November 1, 1981, steelworkers were shocked by U.S. Steel’s announcement that it was purchasing Marathon Oil for more than $6 billion. From 1979 and 1986, U.S. Steel alone, in the Mon Valley alone, eliminated 27,000 steelworker jobs.

Workers in the Mon Valley got a warning of their dark future in 1979, when both LTV and U.S. Steel shut down their mills in nearby Youngstown, OH, two years after Youngstown Sheet & Tube closed its mill. Stout and others from Local 1397 participated in the Youngstown workers’ struggle. Stout credits Ed Mann and John Barbaro, Youngstown local USW leaders, as two of his teachers. Local 1397 later took up leadership of something the Youngstown workers had launched, the Tri-State Conference on Steel (TSCS), a labor-community alliance fighting for jobs in the steel-producing area of western PA, eastern OH, and northern West Virginia. Stout’s friend Charlie McCollester, who was then chief steward of UE Local 610 at the Union Switch & Signal plant in Swissvale, PA, worked with Stout to build TSCS.

The trickle of Mon Valley layoffs started in 1981 and soon became a torrent of job loss. TSCS’s initiatives included food banks to feed laid-off workers’ families, and the Mon Valley Unemployed Committee (MVUC), which continues to this day. MVUC became expert at fighting for unemployment compensation and Trade Adjustment Assistance for individual workers, and in mobilizing concerted action to fight for extensions of those government programs.

TSCS also spawned the Steel Valley Authority (SVA), jointly authorized by municipalities to exercise the right of eminent domain to seize mills and other factories and reopen under new ownership. It won a significant victory in 1982 in the fight to save the unionized Nabisco bakery in Pittsburgh’s East Liberty neighborhood. The threat of seizure through eminent domain, alongside a boycott and other public pressure, forced Nabisco to back away from plans to close. But the company did close the plant in 1998. UE supported the eminent domain tactic, with which Charlie McCollester, Local 610, TSCS and political allies tried to save the Switch & Signal plant. During that fight, the union brought UE Local 277 President Rod Poineau to speak in Pittsburgh. His local had successfully used the threat of eminent domain to hold off (for five years) the closing of Morse Cutting Tool in New Bedford, MA.

Throughout the book, Stout emphasized many people were responsible for the accomplishments of Local 1397, and that its triumphs and tragedies were collective. He introduces us to many of his former co-workers, with mini-biographies of key activists. Although steelmaking in the ‘70s and ‘80s remained a male-dominated industry, Stout makes it clear that in addition to the extraordinary Michele McMills, other women workers played indispensable roles in the struggles he recounts.

Delegates to last year’s UE Convention will remember Mike Stout. He sang and played guitar for us before several of the convention sessions, performing some of the many songs of worker resistance he’s written over the decades. He has performed at other UE conventions, and last year he performed three times at contract negotiation rallies and picket lines for western PA UE locals. He’s a longtime friend of UE, since the big UE Local 610 strike of 1981-82, and in the concluding chapter, he devotes an entire page to explaining why UE is the model of what unions should be.

The book is profusely illustrated with photos of the people and events Stout is describing, as well as cartoons drawn by rank-and-file members that appeared in the 1397 Rank and File newspaper. They text frequently includes Stout’s song lyrics written at the time of events he’s describing, some of them tributes to specific comrades in the struggle.

I’ll give Mike the last word on the importance of this wonderful book: “The only way the union flame could be permanently extinguished at Homestead was by pulling the floor out from underneath us, shutting down the whole thing, and erasing our important historic contributions. My hope and prayer are that millennial workers and union activists will hear about this early history and continue the fight for justice, equality and democracy.”

You can purchase Homestead Steel Mill, The Final Ten Years online from the publisher at pmpress.org. If you’d like to get an autographed first-edition, you can buy it directly from the author. Send your check ($30 paperback, $60 hardcover) to Mike Stout, 4223 Willow Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15234.